I/H Section Calculator

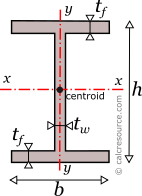

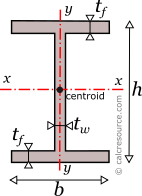

This tool calculates the properties of an I/H cross-section, also known as double-tee, I-beam or I-section. Enter the shape dimensions h, b, tf and tw below. The calculated results will have the same units as your input. Please use consistent units for any input.

h = | |||

b = | |||

tf = | |||

tw = | |||

Geometric properties: | |||

Area = | |||

Perimeter = | |||

Properties related to x-x axis: | |||

Ix = | |||

Sx = | |||

Zx = | |||

Rgx = | |||

ADVERTISEMENT | |||

Properties related to y-y axis: | |||

Iy = | |||

Sy = | |||

Zy = | |||

Rgy = | |||

Other properties: | |||

Iz = | |||

|

ADVERTISEMENT

Definitions

Table of contents

Geometry

The area A and the perimeter P, of an I/H cross-section, can be found with the next formulas:

Moment of Inertia

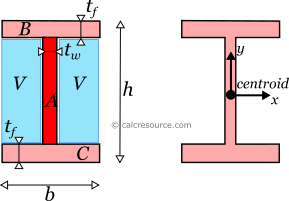

The moment of inertia of an I/H section can be found if the total area is divided into three, smaller subareas, A, B, C, as shown in figure below. The final area, may be considered as the additive combination of A+B+C. However, since the flanges are equal, a more straightforward combination can be (A+B+C+2V)-2V. This way, the moment of inertia of the I/H section, relative to centroidal x-x axis, is determined like this:

where the section height, the width of the flanges, the thickness of the flanges and the thickness of the web.

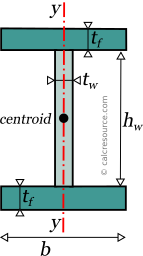

The moment of inertia of the I/H section, around centroidal y-y axis, is found by combining the individual moments of inertia, from the two flanges (subareas B and C) and the web (subarea A). The centroids of these subareas are aligned with the cross-section y axis, and therefore adding them together is acceptable (otherwise we should have employed the parallel axis theorem). The moment of inertia is:

which is simplified to:

where , is the clear web height.

The moment of inertia (second moment or area) is used in beam theory to describe the rigidity of a beam against flexure. The bending moment M applied to a cross-section is related with its moment of inertia with the following equation:

where E is the Young's modulus, a property of the material, and , the curvature of the beam due to the applied load. Therefore, it can be seen from the former equation, that when a certain bending moment M is applied to a beam cross-section, the developed curvature is reversely proportional to the moment of inertia I.

The polar moment of inertia, describes the rigidity of a cross-section against torsional moment, likewise the planar moments of inertia described above, are related to flexural bending. The calculation of the polar moment of inertia around an axis z-z (perpendicular to the section), can be done with the Perpendicular Axes Theorem:

where the and are the moments of inertia around axes x-x and y-y that are mutually perpendicular with z-z and meet at a common origin.

The dimensions of moment of inertia are .

Elastic modulus of I section

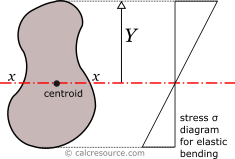

The elastic section modulus of any cross section, for a given axis x-x (centroidal), describes the response of the section under elastic flexural bending, around this axis. It is defined as:

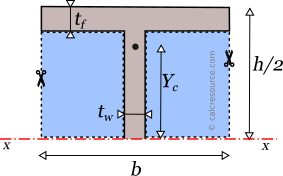

where the moment of inertia of the section around x-x axis and Y the offset of a given section fiber (parallel to the same x-x axis) from centroid. Typically the elastic modulus related to the most distant fiber is of interest. If a cross-section is symmetric (the I-section is) around an axis (e.g. x-x) and its dimension perpendicular to this axis is h, then Y=h/2 and the above formula becomes:

Similarly, for the section modulus , around y-y axis, which, for the I/H section, happens to be axis of symmetry too, the above definitions are written as:

If a bending moment is applied around axis x-x, the section will respond with normal stresses, varying linearly with the distance from the neutral axis (which under elastic regime coincides to the centroidal x-x axis). Over the neutral axis the stresses are by definition zero. Absolute maximum , will occur at the most distant fiber, with magnitude given by the formula:

From the last equation, the section modulus can be considered for flexural bending, a property analogous to cross-sectional A, for axial loading. For the latter, the normal stress is F/A.

The dimensions of section modulus are .

Plastic modulus of I section

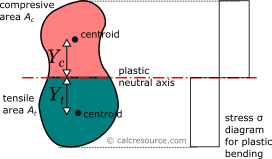

The plastic section modulus is similar to the elastic one, but defined with the assumption of full plastic yielding, of the cross section, as a result of flexural bending. In that case, the whole section is divided in two parts, one in tension and one in compression, each under uniform stress field. For materials with equal tensile and compressive yield stresses, this leads to the division of the section into two equal areas, in tension and in compression, separated by the neutral axis. This is a result of equilibrium of internal forces in the cross-section, under plastic bending. Indeed, the compressive force would be , assuming the yield stress is equal to , in compression, and that the material over the entire compressive area has yielded (thus the stresses are equal to everywhere). Similarly, the tensile force would be , using the same assumptions. Enforcing equilibrium:

The axis is called plastic neutral axis, and for non-symmetric sections, is not the same with the elastic neutral axis (which again is the centroidal one). The I-section however, is indeed a symmetric cross-section, both around strong and weak axis. As a result the I-section plastic neutral axis coincides with the elastic one.

Around x axis

For an I-section, the x-x axis, that is parallel to flanges, is typically the strong axis of the cross-section. The plastic modulus of a cross-section is given by the general formula (assuming bending around x axis):

where , the distance of the centroid of the compressive area , from the plastic neutral axis, and , the respective distance of the centroid of the tensile area .

For the case of an I-beam, the plastic neutral axis passes through centroid, dividing the whole section into two equal parts. Taking advantage of symmetry it is: . Finding these centroids, is straightforward. We will consider the part above the neutral axis (assumed in compression). The centroid of this part is located at a distance from the plastic neutral axis. It is convenient to assume that the whole part, is equivalent to the difference between an outer rectangle, having dimensions, b and h/2 minus two smaller rectangles, as shown in the next figure. The centroid of the whole part is then found, by making the static moment of inertia (first moment of area) equal between the whole part and the difference of its outer and the smaller rectangular areas. Remember that the examined part features half the total section area:

where , the clear web height.

Taking into consideration that (due to symmetry) and given that , the plastic modulus, of an I-section, around x axis, is calculated like this:

One may wonder why we didn't find the plastic moduli of the flanges and the web around their respective local centroidal axes, and then use a parallel axis theorem, to get the respective moduli around the section centroid, similarly to the procedure we follow for the moment of inertia. Unfortunately, there is no parallel axes theorem for the calculation of plastic modulus. It is not possible to find the plastic modulus around a parallel axis, without recalculating it from start.

Around y axis

For an I-section, the y-y axis, that is perpendicular to flanges, is typically the weak axis of the cross-section. Instead of finding the centroid of the compressive and tensile areas, these time we will follow a different approach, in order to find the plastic modulus. It is not difficult to prove that the plastic modulus of a rectangle, with dimensions b and h, around a centroidal axis, parallel to b is:

The whole I-section is now considered a combination of three rectangles, two for the flanges and one for the web, as illustrated in the following figure.

All three rectangles share the same centroidal axis, which is also the y-axis, of the entire cross section. It would be not possible to proceed otherwise. Applying the above formula, for each one of these rectangles, we get the plastic modulus, of the entire I-section, around y axis:

where .

Radius of gyration

Radius of gyration of a cross-section, relative to an axis, is given by the formula:

where I the moment of inertia of the cross-section about the same axis and A its area. The dimensions of radius of gyration are . It describes how far from centroid the area is distributed. Small radius indicates a more compact cross-section. Circle is the shape with minimum radius of gyration, compared to any other section with the same area A. The I-section, would have considerably higher radius of gyration, particularly around its x-x axis, because much of its cross-sectional area is located far from the centroid, at the two flanges.

I/H section formulas

The following table, lists the main formulas, related to the mechanical properties of the I/H section (also called double-tee section).

I/H section properties | |

|---|---|

| Quantity | Formula |

| Area: | |

| Perimeter: | |

| Moments of inertia | |

| Elastic modulus: | |

| Plastic modulus: | |

where: | |