Moment of Inertia of a Rectangular Tube

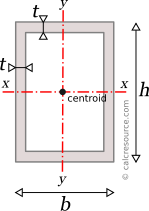

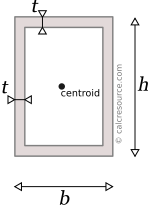

This tool calculates the moment of inertia I (second moment of area) of a rectangular tube (rectangular hollow section). Enter the shape dimensions 'b', 'h' and 't' below. The calculated results will have the same units as your input. Please use consistent units for any input.

h = | |||

b = | |||

t = | |||

Results: | |||

ADVERTISEMENT

Definitions

The moment of inertia of a rectangular tube with respect to an axis passing through its centroid, is given by the following expression:

where, b is the tube total width, and specifically its dimension parallel to the axis, and h is the height (more specifically, the dimension perpendicular to the axis) and t is the thickness of the walls. The internal, hollow width bh and height hh are equal to b-2t and h-2t, respectively.

The moment of inertia of a rectangle with respect to a centroidal axis perpendicular to its base, can be found, by alternating dimensions b and h, in the first equation above:

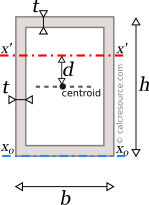

Parallel Axes Theorem

The moment of inertia of any shape, in respect to an arbitrary, non centroidal axis, can be found if its moment of inertia in respect to a centroidal axis, parallel to the first one, is known. The so-called Parallel Axes Theorem is given by the following equation:

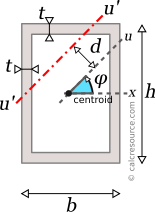

where I' is the moment of inertia in respect to an arbitrary axis, I the moment of inertia in respect to a centroidal axis, parallel to the first one, d the distance between the two parallel axes and A the area of the shape, equal to , in the case of a rectangular tube.

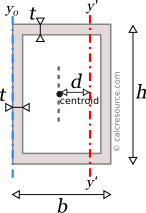

For the product of inertia Ixy, the parallel axes theorem takes a similar form:

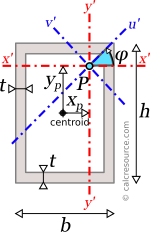

where Ixy is the product of inertia, relative to centroidal axes x,y (=0 for the rectangular tube, due to symmetry), and Ixy' is the product of inertia, relative to axes that are parallel to centroidal x,y ones, having offsets from them and respectively.

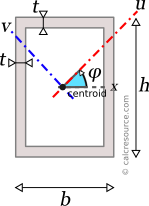

Rotated axes

For the transformation of the moments of inertia from one system of axes x,y to another one u,v, rotated by an angle φ, the following equations are used:

where Ix, Iy the moments of inertia about the initial axes and Ixy the product of inertia. Iu, Iv and Iuv are the respective quantities for the rotated axes u,v. The product of inertia Ixy of a rectangular tube, about centroidal x,y axes, is zero, because x and y are also symmetry axes.

Principal axes

In principal axes, that are rotated by an angle θ relative to original centroidal ones x,y, the product of inertia becomes zero. Because of this, any symmetry axis of the shape, is also a principal axis. The moments of inertia about principal axes, are called principal moments of inertia, and are the maximum and minimum ones, for any angle of rotation of the coordinate system. For a rectangular tube, axes x and y are symmetry axes and therefore, they define the principal axes of the shape. As a result, Ix and Iy are the principal moments of inertia of the rectangle.

Dimensions

The dimensions of moment of inertia (second moment of area) are .

Mass moment of inertia

In Physics the term moment of inertia has a different meaning. It is related with the mass distribution of an object (or multiple objects) about an axis. This is different from the definition usually given in Engineering disciplines (also in this page) as a property of the area of a shape, commonly a cross-section, about the axis. The term second moment of area seems more accurate in this regard.

Applications

The moment of inertia (second moment or area) is used in beam theory to describe the rigidity of a beam against flexure (see beam bending theory). The bending moment M applied to a cross-section is related with its moment of inertia with the following equation:

where E is the Young's modulus, a property of the material, and κ the curvature of the beam due to the applied load. Beam curvature κ describes the extent of flexure in the beam and can be expressed in terms of beam deflection w(x) along longitudinal beam axis x, as: . Therefore, it can be seen from the former equation, that when a certain bending moment M is applied to a beam cross-section, the developed curvature is reversely proportional to the moment of inertia I. Integrating curvatures over beam length, the deflection, at some point along x-axis, should also be reversely proportional to I.