How to find the centroid of an area

Table of contents

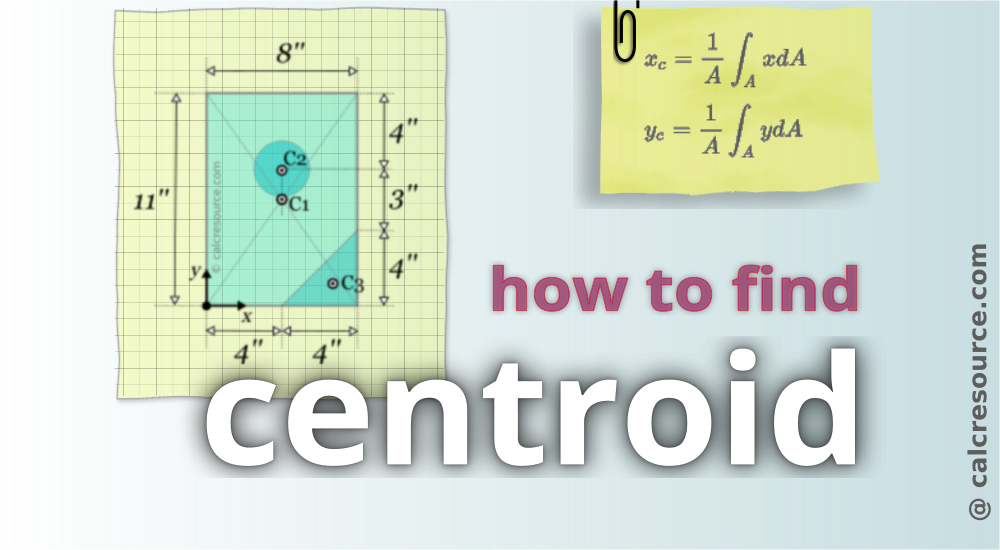

Integration formulas

The centroid of any shape can be found through integration, provided that its border is described as a set of integrate-able mathematical functions. Specifically, the centroid coordinates xc and yc of an area A, are provided by the following two formulas:

The integral term in the last two equations is also known as the 'static moment' or 'first moment' of area, typically symbolized with letter S. Therefore, the last equations can be rewritten in this form:

where and .

The area A can also be found through integration, if that is required:

Steps for finding centroid using integration formulas

The steps for the calculation of the centroid coordinates, xc and yc , through integration, are summarized to the following:

- Select a coordinate system, (x,y), to measure the centroid location with.

- Select an appropriate, and convenient for the integration, coordinate system. It can be the same (x,y) or a different one. Called hereafter working coordinate system.

- Describe the borders of the shape and the x, y variables according to the working coordinate system.

- Integrate, substituting, where needed, the x and y variables with their definitions in the working coordinate system.

The application of the procedure will become clear with the examples later in the article.

Composite Areas

For composite areas, that can be decomposed to a finite number of simpler subareas, and provided that the centroids of these subareas are available or easy to find, then the centroid coordinates of the entire area can be calculated through the following formulas:

where is the surface area of subarea i, and the centroid coordinates of subarea i. The sum is equal to the total area A. The sums that appear in the two nominators are the respective first moments of the total area: and .

Steps to find the centroid of composite areas

The steps for the calculation of the centroid coordinates, xc and yc , of a composite area, are summarized to the following:

- Select a coordinate system, (x,y), to measure the centroid location with.

- Decompose the total area to a number of simpler subareas.

- Find the centroid of each subarea in the x,y coordinate system.

- Find the surface area and the static moment of each subarea.

- Find the total area A and the sum of static moments Sx and Sy, in respect to axes x, y.

- Calculate the centroid coordinates, and .

For step 1, it is permitted to select any arbitrary coordinate system of x,y axes, however the selection is mostly dictated by the shape geometry. The final centroid location will be measured with this coordinate system, i.e. xc will be the distance of the centroid from the origin of axes, in the direction of x, and similarly yc will be the distance of the centroid from the origin of axes, in the direction of y. Typically, a characteristic point of the shape is selected as the origin, like a corner point of the border or a pole for curved shapes.

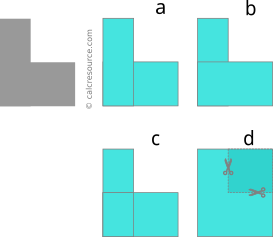

With step 2, the total complex area should be subdivided into smaller and more manageable subareas. This can be accomplished in a number of different ways, but more simple and less subareas are preferable. The requirement is that the centroid and the surface area of each subarea can be easy to find. However, if the process of finding the centroid is performed in the context of finding the moment of inertia of the shape too, additional considerations should be made for the selection of subareas. Read our article about finding the moment of inertia for composite areas (available here), for more detailed explanation.

Sometimes, it may be preferable to define negative subareas, that are meant to be subtracted from other bigger subareas to produce the final shape.

In step 3, the centroids of all subareas are determined, in respect to the selected, at step 1, coordinate system. For subarea i, the centroid coordinates should be and . The work we have to do in this step heavily depends on the way the subareas have been defined in step 2. Centroid tables from textbooks or available online can be useful, if the subarea centroids are not apparent. You may find our centroid reference table helpful too.

In step 4, the surface area of each subarea is first determined and then its static moments around x and y axes, using these equations:

where, Ai is the surface area of subarea i, and , the centroid coordinates of subarea i, that should be known from step 3.

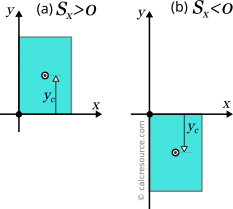

The following figure demonstrates a case where the same rectangular area may have either positive or negative static moment, based on the location of its centroid, in respect to the axis. The sign of the static moment is determined from the sign of the centroid coordinate. For the rectangle in the figure, if (case b) then the static moment should be negative too.

If a subarea is negative though (meant to be cutout) then it must be assigned with a negative surface area Ai . Consequently, the static moment of a negative area will be the opposite from a respective normal (positive) area.

In step 5, the process is straightforward. In order to find the total area A, all we have to do is, add up the subareas Ai , together.

Similarly, in order to find the static moments of the composite area, we must add together the static moments Sx,i or Sy,i of all subareas:

Step 6, is the final one, and leads to the wanted centroid coordinates:

Example 1: centroid of a right triangle using integration formulas

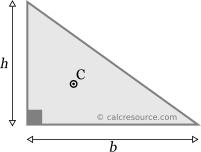

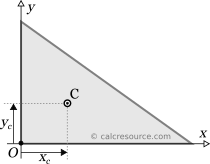

Derive the formulas for the centroid location of the following right triangle.

Step 1

We select a coordinate system of x,y axes, with origin at the right angle corner of the triangle and oriented so that they coincide with the two adjacent sides, as depicted in the figure below:

Step 2

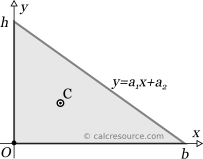

For the integration we choose the same coordinate system, as defined in step 1.

Step 3

The triangular area is bordered by three lines:

- The x axis, i.e.

- The y axis, i.e.

- The inclined line passing through points (b,0) and (0,h). Let's assume the line equation has the form: . Substituting point (0,h) to the line equation we get: . Substituting point (b,0), and the a2=h, we get: . Therefore, we have found the line equation in terms of the triangle side lengths, as:

Step 4a

First, we'll find the yc coordinate of the centroid, using the formula: . The first moment of area is given by the double integral:

where, are the lower and upper bounds of the area in terms of x variable and , the respective bounds in terms of the y variable. First, we'll integrate over y. So the lower bound, in terms of y is the x axis line, with and the upper bound is the inclined line, given by the equation, we've already found: . Finding the integral is straightforward:

So, we have found the first moment for an area bounded between the x axis and the inclined line, going on ad infinitum (because no x bounds are imposed yet). Next, we have to restrict that area, using the x limits that would produce the wanted triangular area. These are and . Therefore, the integration over x, that will produce the final moment of the area, becomes:

The only thing remaining is the area A of the triangle. That is available through the formula:

Finally, the centroid coordinate yc is found:

Step 4b

The process for finding the coordinate of the centroid is pretty similar. This time we'll need the first moment of area, around y axis, :

We integrate over y:

And then over x, to get the final first moment of area:

And finally, we find the centroid coordinate xc:

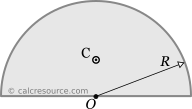

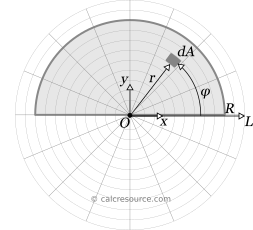

Example 2: centroid of semicircle using integration formulas

Derive the formulas for the location of semicircle centroid

Step 1

The coordinate system, to locate the centroid with, can be anything we want. In order to take advantage of the shape symmetries though, it seems appropriate to place the origin of axes x, y at the circle center, and orient the x axis along the diametric base of the semicircle.

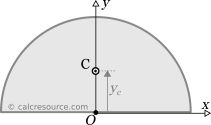

Because the shape is symmetrical around axis y, it is evident that centroid should lie on this axis too. In other words:

In the next steps we'll need to find only coordinate yc.

Step 2

We must decide on the working coordinate system. It could be the same Cartesian x,y axes, we have selected for the position of centroid. Because the shape features a circular border though, it seems more convenient to select a polar system, with its pole O coinciding with circle center, and its polar axis L coinciding with axis x, as depicted in the figure below. The independent variables are r and φ. Specifically, for any point of the plane, r is the distance from pole and φ is the angle from the polar axis L, measured in counter-clockwise direction.

With this coordinate system, the differential area dA now becomes: , where is the differential arc length for differential angle .

Step 3

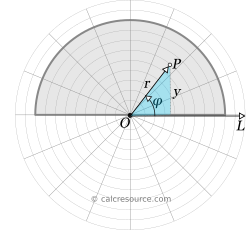

In terms of the polar coordinates , the semicircle shape, is bounded through these limits:

Also, we 'll need to express coordinate y, that appears inside the integral for yc , in terms of the working coordinates, . Employing the highlighted right triangle in the figure below and using simple trigonometry we find: .

Step 4

Using the aforementioned expressions for and , the definite integral for the first moment of area, , of the semicircle becomes:

First, we integrate over variable φ.

The anti-derivative for is: , and as a result, the integral inside the parentheses becomes:

Substituting to the expression of Sx, we now have to integrate over variable r:

The area of the semicircle is:

Finally, the centroid coordinate yc can be found:

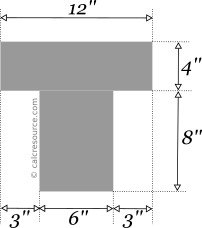

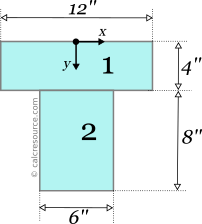

Example 3: Centroid of a tee section

Find the centroid of the following tee section

This is a composite area. The procedure for composite areas, as described above in this page, will be followed.

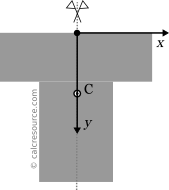

Step 1

We place the origin of the x,y axes to the middle of the top edge. The x axis is aligned with the top edge, while the y is axis is looking downwards.

Due to symmetry around the y axis, the centroid should lie on that axis too. In other words:

In the remaining we'll focus on finding the centroid coordinate yc.

Step 2

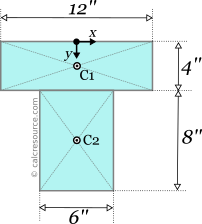

This is a composite area that can be decomposed to more simple subareas. We choose the following pattern, where the tee is decomposed to two rectangles, one for the top flange and one for the web. We'll refer to them as subarea 1 and subarea 2, respectively.

Step 3

The centroids of each subarea will be determined, using the defined coordinate system from step 1. For subarea 1:

And for subarea 2:

Step 4

The surface areas of the two subareas are:

The static moments of the two subareas around x axis can now be found:

Step 5

The total area of the tee shape is:

The static moment of the entire tee area, around x axis, is:

The above calculations can be summarized in a table, like the one shown here:

| Area | yc,i | Ai | Sx,i=Aiyc,i |

|---|---|---|---|

| (in) | (in2) | (in3) | |

| 1 | 2 | 48 | 96 |

| 2 | 8 | 48 | 384 |

| Total | 96 | 480 |

Step 6

Knowing the total static moment, around x axis, , and the total surface area, , we are now in position to find the centroid coordinate, :

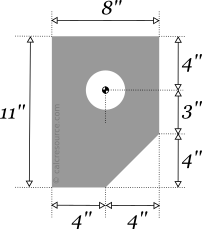

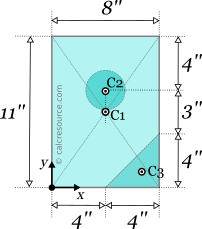

Example 4: plate with a hole

Find the centroid of the following plate with a hole. The hole radius is r=1.5''.

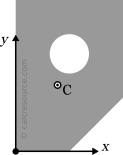

Step 1

We place the origin of the x,y axes to the lower left corner, as shown in the next figure. We are free to choose any point we want, however a characteristic point of the shape (like its corner) is convenient, because we'll find the resulting centroid coordinates xc and yc in respect to that point.

Step 2

This is a composite area that can be decomposed to a number of simpler subareas. Among many different alternatives we select the following pattern, that features only three elementary subareas, named 1, 2 and 3. In particular, subarea 1 is a rectangle, subarea 2 is a circular cutout, characterized as negative subarea, and similarly subareas 3 is a triangular cutout that is also a negative subarea.

Step 3

The centroids of each subarea we'll be determined, using the defined coordinate system from step 1. For subarea 1:

For subarea 2:

For subarea 3:

Step 4

The surface areas of the three subareas are:

The static moments of the three subareas, around x axis, can now be found:

The static moments around y axis are:

Step 5

The total area of the shape is:

The static moments of the entire shape, around axis x, is:

And around axis y:

The above calculation steps can be summarized in a table, like the one shown here:

| Area | xc,i | yc,i | Ai | Sx,i=Aiyc,i | Sy,i=Aixc,i |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (in) | (in) | (in2) | (in3) | (in3) | |

| 1 | 4 | 5.5 | 88 | 484 | 352 |

| 2 (negative) | 4 | 7 | -7.069 | -49.48 | -28.27 |

| 3 (negative) | 1.333 | 6.667 | -8 | -10.67 | -53.33 |

| Total | 72.931 | 423.85 | 270.40 |

Step 6

We can now calculate the coordinates of the centroid: